Exploring Fauvism: Wild Beasts, Pure Color, and the Birth of Modern Expression — History of Art #12

Fauvism was the first modern avant-garde movement in art. It emerged in France between 1905 and 1908, and its principles continued to influence artists even in later works. Unlike some other movements, Fauvism was not defined by formal manifestos. Instead, it was recognized as a style by critics.

The name "Fauves," meaning "wild beasts," came from an offhand remark by the art critic Louis Vauxcelles. In 1905, while reviewing the Salon d'Automne exhibition, he contrasted the traditional sculptures of Albert Marquet (a child's torso and a female bust) with the vivid, intense colors of the young painters. He famously wrote "Donatello among the wild beasts!" in the magazine Gil Blas on October 17, 1905. The label stuck, and the artists of the movement were forever known as Fauves.

Ironically, the same critic also coined the term "Cubism," criticizing Braque's paintings for consisting of "little cubes." Two seemingly mocking comments became the names of two of the most influential art movements in history.

Fauvist artists emphasized individual expression above all, believing that a painter should develop and assert their own artistic personality. Color became a primary means of expression, often inspired by Paul Gauguin’s use of abstract color. They also drew inspiration from folk art, Mexican art, African sculpture, and early Renaissance painting, while taking cues from the work of Van Gogh, Cézanne, and Gauguin.

The movement developed from three main groups of artists. The first came from Gustave Moreau’s studio at the École des Beaux-Arts and the Académie Carrière in Paris, including Henri Matisse, Albert Marquet, Charles Camoin, Jean Puy, and Henri Manguin. The second group, known as the Chatou duo, included Maurice de Vlaminck and André Derain. The third group, called the Le Havre trio, consisted of Othon Friesz, Raoul Dufy, and Georges Braque. Among them, Henri Matisse emerged as the most prominent figure of the movement.

Together, these artists sought a new artistic language focused on color rather than realistic representation. Their bold, often unexpected use of color broke away from traditional depictions of the world, emphasizing personal vision and emotional impact over naturalistic accuracy.

“I do not literally paint that table, but the emotion it produces upon me.“ — Henri Matisse

The subject matter explored by "wild beasts" was incredibly diverse, but above all, it was intended to directly appeal to the viewer's senses. Fauvist artists created in a wide range of genres, including portraits, nudes, landscapes, and still lifes.

Rather than seeking faithful representation, Fauvist painters used color and form to convey emotion and personal experience. By rejecting naturalistic conventions, they transformed familiar subjects into expressive compositions that challenged traditional ways of seeing and laid the groundwork for the development of modern art.

1) Inspirations

“My choice of colors does not rest on any scientific theory; it is based on observation, on feeling, on the very nature of each experience.“ — Henri Matisse

The Fauves drew inspiration from the Impressionists and Neo-Impressionists, employing bold brushstrokes as well as techniques such as pointillism and divisionism. Pointillism involves applying small, distinct dots of pure color that blend optically in the viewer's eye to form an image, while divisionism relies on separating colors into broader strokes or patches placed side by side to achieve a luminous effect.

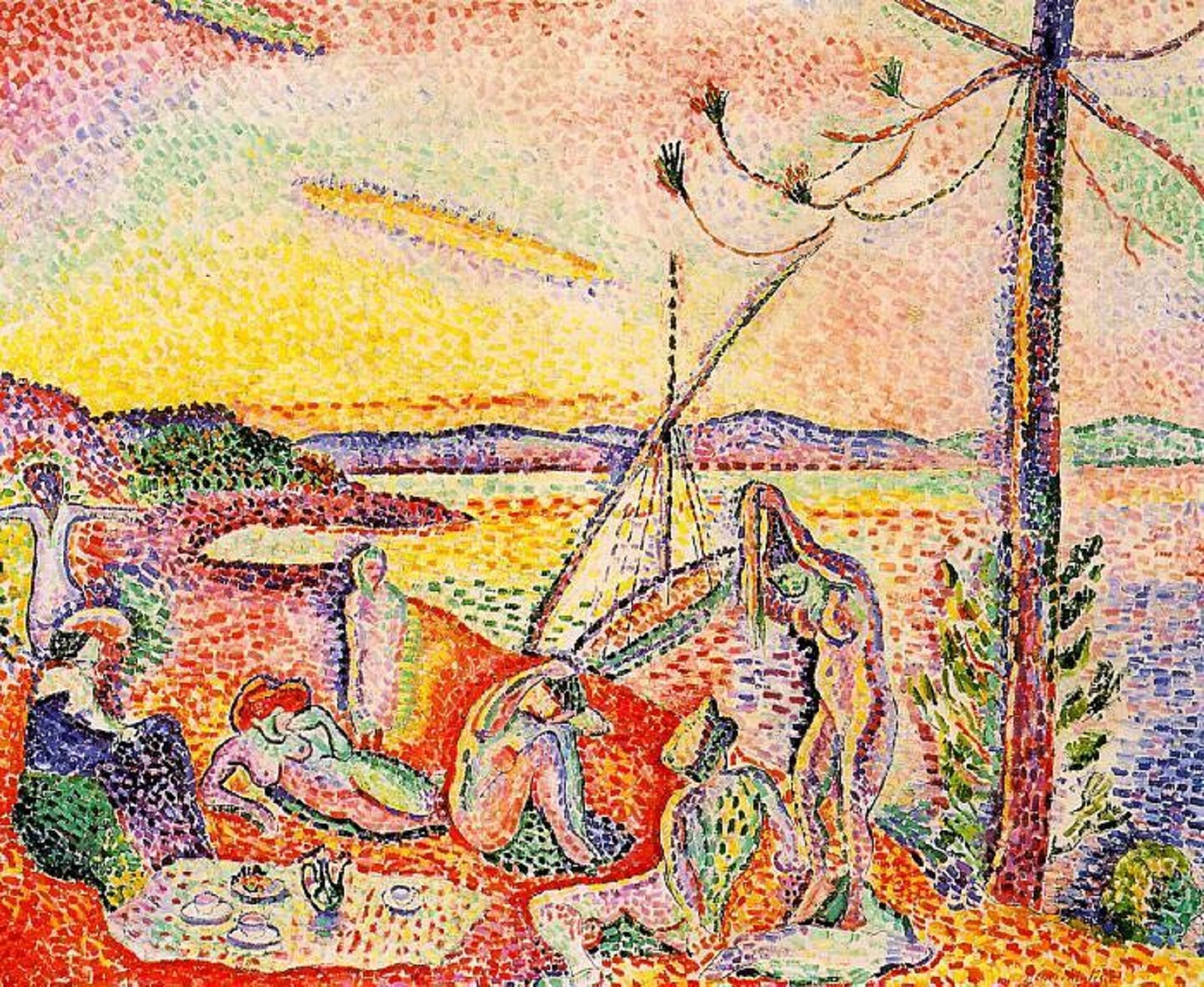

A good example of pointillist technique, the application of paint in small dots and strokes, can be seen in Henri Matisse’s work, “Luxury, Calm and Pleasure” (1904). Matisse, the leading figure of the Fauvism movement, uses a fiery mix of oranges, yellows, greens, and purples, creating a vibrant, almost overwhelming effect. Unlike Neo-Impressionists like Georges Seurat, he avoids the subtle blending of colors, emphasizing bold, energetic contrasts instead.

Henri Matisse, Luxury, Calm and Pleasure, 1904 via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

The canvas was painted in Paris during the winter of 1904-1905, based on sketches Matisse created that summer in Saint-Tropez while working alongside Paul Signac, a prominent Neo-Impressionist. The painting retains a sketchy, energetic quality, achieved through Matisse's technique of applying paint in fragmented brushstrokes of varying widths that create a vibrating, luminous surface.

Though inspired by Neo-Impressionist methods, Matisse refused to follow their scientific principles rigidly. Instead, he prioritized giving color its greatest possible intensity and autonomy, abandoning strict chromatic rules. In doing so, he elevated what might have been an ordinary genre scene into a symbolic composition.

This shift is underscored by the painting's title, taken from Charles Baudelaire's poem Invitation to the Voyage:

"There all is order and beauty, Luxury, peace, and pleasure."

The composition is divided into three distinct planes. The foreground features nude figures, both men and women, picnicking along the seashore. Four figures sit or recline, three stand upright, and one dries her long hair. The middle ground is occupied by a bay stretching toward the horizon, which is enclosed by a band of gentle hills in the background.

The entire arrangement relies on a deliberate interplay of vertical lines (the tree on the right, the boat's mast), horizontal lines (the horizon), diagonal lines (the shoreline), and numerous curves that define the contours of the figures.

As we mentioned earlier, the Fauves drew inspiration from Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, pioneers of a new approach to color in painting. Van Gogh rejected traditional chiaroscuro modeling, tonal transitions, and half-tones in his work. Color became his primary means of expression. In his paintings, intense hues contrast directly with one another. Paint is applied thickly, creating rich textures with visible brushstrokes. Van Gogh himself advised using raw colors and occasionally leaving areas unfinished or unpainted. His works convey the artist's emotions and psychological states, with deformation of forms used to heighten the impact.

Inspired by Gauguin, the Fauves rejected the illusionistic, imitative representation of the world associated with traditional painting. Moving away from established conventions, they embraced Gauguin's theory of Synthetism, which involved using flat patches of intense color outlined with dark contours. This approach, known as cloisonnism, was developed in the late 19th century by Gauguin and painters associated with the Pont-Aven school. It emphasized simplified forms and flat color areas, often surrounded by bold outlines. Following Gauguin's example, the Fauves also recognized the significance of primitive and non-European art.

Van Gogh's works were exhibited in 1901 at the Bernheim-Jeune gallery in Paris and in 1906 at the Salon des Indépendants, an annual exhibition held in Paris since 1884. The Salon des Indépendants was created as a protest against the official Salon, whose jury rejected many submitted works. In 1905, the same venue hosted an exhibition of Paul Gauguin's work.

André Derain, The Pool of London, 1906 via Wikipedia, public domain

An example of these influences can be seen in André Derain's "The Pool of London" (1906). At the suggestion of art dealer Ambroise Vollard, Derain traveled to London in 1906 to create a series of paintings, following the commercial success of Claude Monet's earlier London works.

The painting depicts a stretch of the River Thames as seen from London Bridge, with cargo ships, cranes, and the Tower Bridge in the distance. Derain abandons naturalistic color entirely. The water blazes in strokes of orange, pink, and electric blue, while the sky shifts from green to violet.

Bold, unblended hues are applied directly to the canvas, transforming the gritty industrial scene into a vibrant, joyful vision. The paint is applied thickly, straight from the tube, creating a rough texture with visible brushwork. Dark outlines define the shapes of boats and buildings, echoing Gauguin's cloisonnist technique and flat color planes, while the energetic application recalls Van Gogh's emotional intensity.

Despite the industrial subject matter, Derain prioritizes personal expression over objective representation, marking Fauvism's embrace of subjectivity in art.

“The substance of painting is light“ — André Derain

It’s worth adding that Derain believed that color and luminosity are the core elements of painting, rather than mere representation of objects. For the Fauves, the canvas became a space for capturing the essence of light itself.

Combining the innovations of Impressionism, Neo-Impressionism, Van Gogh, and Gauguin, the Fauves freed color from its descriptive function, creating a visual language in which color corresponded solely to the artist's inner vision, not to the external world.

2) Features of Fauvism

“I heightened all my tonal values and transposed into an orchestration of pure color every single thing I felt.“ — Maurice de Vlaminck

In terms of subject matter, the artists focused primarily on portraits and landscapes, rejecting historical, mythological, and allegorical compositions. The Fauvist palette was dominated by pure, highly intense colors arranged in bold contrasts, with saturated reds often placed alongside greens or yellows. Although nature served as a point of departure, Fauvist works were not intended to be descriptive but rather to convey the emotional experience evoked by a selected fragment of nature.

This approach led to a deliberate departure from naturalistic color, resulting in red tree trunks or vividly colored faces in portraits. The Fauves abandoned traditional perspective and spatial illusion, flattening forms to emphasize the two-dimensional surface of the canvas. Chiaroscuro and three-dimensional modeling were rejected in favor of uniform color intensity across the entire composition.

Their work was characterized by rapid execution and strong visual impact. Dark, often black, outlines defined areas of color, while simplified forms were reduced to basic shapes that merely suggested objects. Line functioned primarily as a decorative and structural element and was secondary to color, the most important means of expression within the movement.

People and objects appeared not as subjects to be realistically represented, but as opportunities for inventive color relationships and rhythmic patterns. Rather than copying what they observed, the Fauves sought to create new visual experiences that appealed directly to the viewer’s senses. Within this approach, they produced portraits, nudes, landscapes, and still lifes.

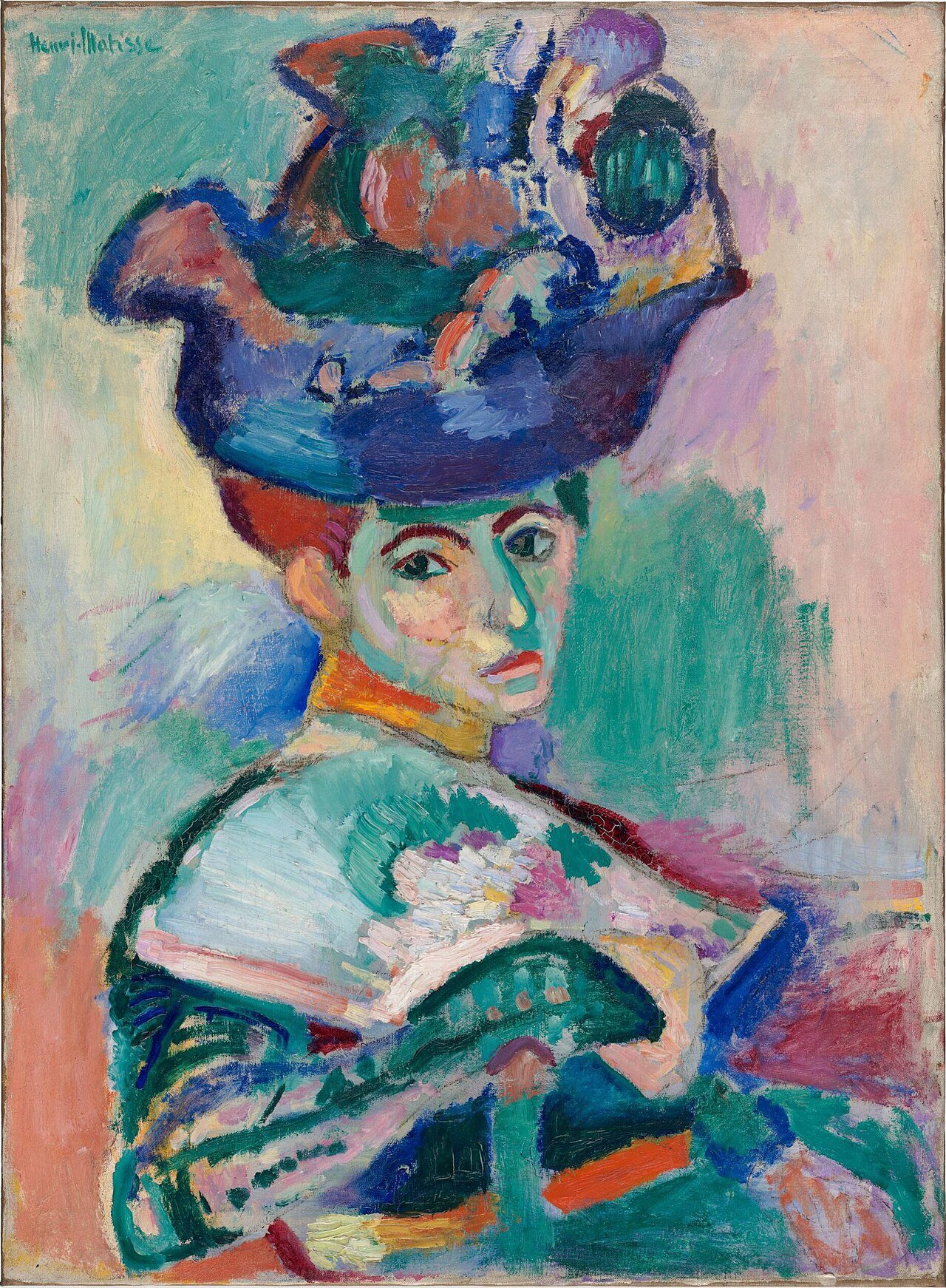

Henri Matisse, Woman with a Hat, 1905 via Wikipedia, public domain

In 1905, Matisse painted “Woman with a Hat,” a portrait of his wife Amélie seated in a chair with one hand resting on its armrest. The bust is shown in profile, while the face is rendered in three-quarter view. Facial features are simplified: brown arcs define the eyebrows, the eyes are indicated schematically in black, and the mouth is suggested by two strokes of red and pink. Thick black lines emphasize the contours of the hat and selected parts of the body, including the arm and hand.

The woman’s head is crowned by a large violet hat decorated with multicolored flowers and feathers arranged above one another. The hat visually dominates the sitter’s delicate face, which is modeled with yellows and oranges contrasted with greens that mark the shadowed areas. The face is built from non-naturalistic colors, with green and orange areas placed side by side and accented with pink and yellow.

The painting illustrates the key principles of Fauvism. Matisse departs from naturalistic color and treats the face not as a subject for realistic representation, but as a field for color experimentation. Complementary colors, such as green and red or violet and yellow, are placed next to each other to create strong visual contrast. Instead of using chiaroscuro to model form, Matisse maintains an even intensity of color across the composition, emphasizing the flat surface of the canvas.

Dark outlines define areas of color, recalling the cloisonnist approach associated with Gauguin, while simplified facial features reduce the figure to basic forms. When the painting was shown at the 1905 Salon d’Automne, it shocked critics and viewers because of its clear rejection of traditional portrait conventions. Rather than depicting his wife’s appearance, Matisse focused on expressing his personal and sensory response, creating a new type of portrait that appealed directly to the viewer’s perception.

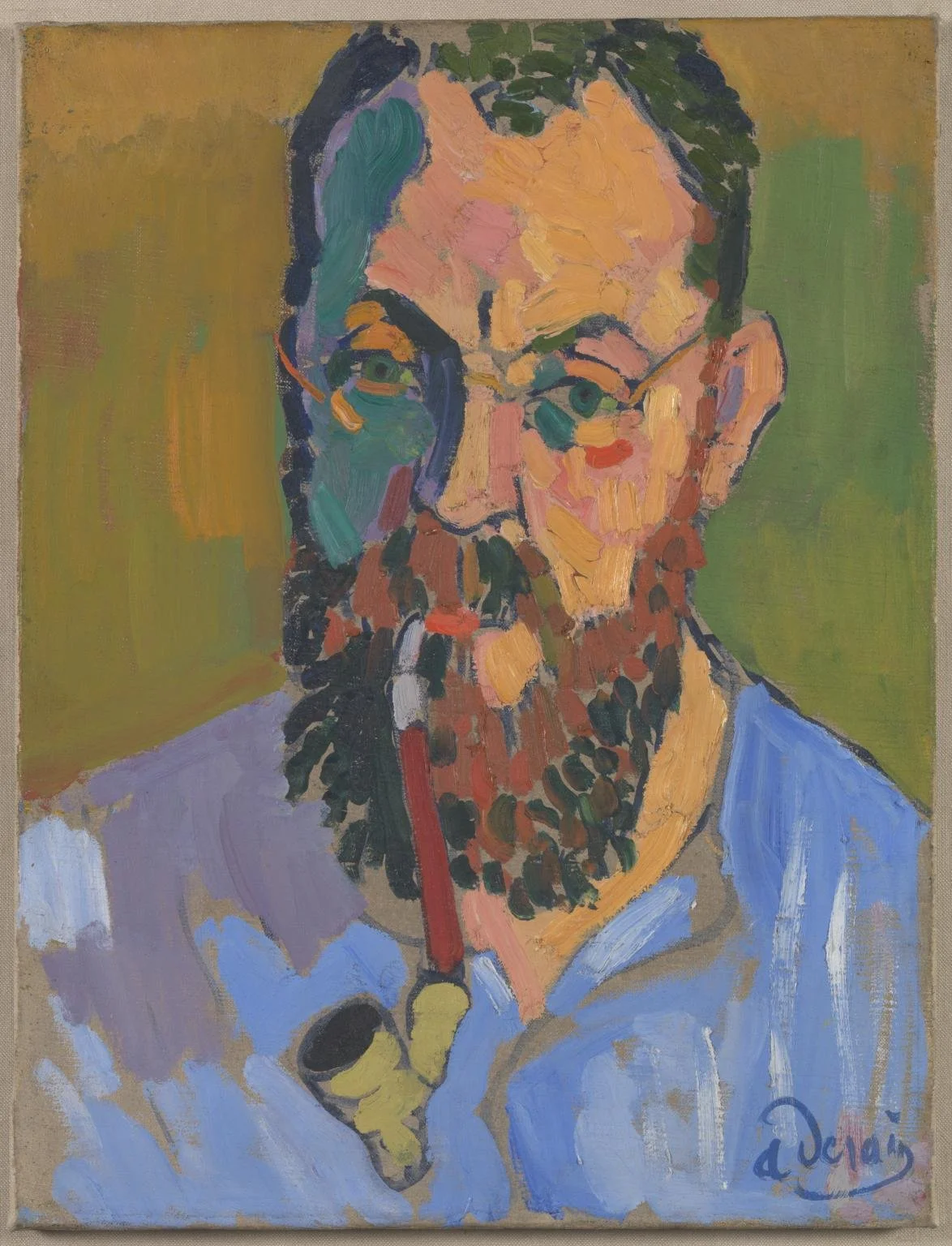

It is also worth noting that in the same year André Derain painted “Portrait of Matisse,” depicting his friend and artistic partner at a crucial moment in the development of Fauvism.

André Derain, Portrait of Matisse, 1905 via Wikipedia, public domain

In the portrait, Matisse’s head is slightly tilted to the left. One side of the face is clearly illuminated, while the other remains in shadow, an effect created primarily through color rather than light. Warm yellows and oranges dominate the lit side of the face, while cool blues and blue-greens define the shaded areas. This strong color contrast replaces traditional chiaroscuro and gives the face a clear structural division.

The shape of the face is emphasized in places by dark contours. Short, dark hair and a reddish-black beard frame the head and separate it from the background. These elements strengthen the outline of the figure and contribute to the clarity of the composition. The background and the figure are closely connected through color, with no attempt to create deep space or realistic perspective.

Rather than aiming for realistic likeness, Derain uses color to express character and presence. The portrait is built almost entirely through dense areas of color, with only minimal use of line. Facial features are simplified, yet the sitter remains immediately recognizable. Matisse’s calm gaze and composed expression suggest introspection and authority, reflecting his role as a leading figure among the Fauves.

The painting reflects not only Derain’s developing style but also the close artistic relationship between the two artists. Derain and Matisse worked together and exchanged ideas, particularly during the summer of 1905, when their experiments with color intensified. In this portrait, Derain presents Matisse not simply as a model, but as a symbol of the new artistic direction they were shaping together. Through its bold use of color and simplified form, “Portrait of Matisse” captures both the individuality of the artist and the broader spirit of Fauvist experimentation.

As previously mentioned in relation to André Derain’s “The Pool of London” (1906), Fauvist painters often distorted traditional perspective. A clear and characteristic example of this approach can already be found in Henri Matisse’s “Open Window” from 1905.

Henri Matisse, The Open Window, 1905 via Wikipedia, public domain

Beyond the building interior, Matisse presents a fragment of a seascape with small boats floating on gently moving water. The interior elements included in the composition are painted in highly saturated and contrasting colors, such as deep pinks, greens, and blues, which correspond closely with the color range of the distant view. The window shutters that frame the composition on both sides are built from intense oranges and reds. The only element that clearly separates itself from the rest of the painting is the upper part of the window frame, rendered in black with firm, decisive brushstrokes.

In this composition, it is difficult to distinguish traditional spatial planes. Instead, the painting can be divided into several horizontal zones. Closest to the viewer is the open window seen from inside the room. On the windowsill, potted plants are placed, painted with strokes of yellow, red, blue, and green, similar to the climbing plant that surrounds the window opening. This zone of vegetation is separated from the next area by a dark horizontal line.

Above it appears a second band filled with water and boats, which is in turn separated by another horizontal line, suggesting the horizon. The uppermost zone contains the sky and clouds. Through this banded composition, Matisse creates a sense of depth not by linear perspective, but by stacking visual zones vertically. Elements that are meant to appear farther away are placed higher within the picture plane, a principle known since antiquity. In this way, “Open Window “ demonstrates a Fauvist rejection of traditional perspective in favor of a simplified, color-driven structure of space.

It’s also worth mentioning Maurice de Vlaminck, another key representative of Fauvism, who worked primarily with landscapes, still lifes, and floral subjects. His paintings are characterized by intense, vivid colors, dynamic compositions, and simplified forms. These qualities later became important in his transition toward Cubism.

In “Landscape with Red Trees,” Vlaminck demonstrates a distinctive approach to space by using a type of overlapping perspective, in which elements placed in the foreground partially obscure those in the background, creating a sense of depth.

Maurice de Vlaminck, Landscape with Red Trees, 1906 via Wikipedia, public domain

At the center of the composition are the red trees that give the painting its title. Their striking color is deliberately unrealistic and immediately draws the viewer’s attention. The shapes of the trees, including the thinner trunks in the background, are outlined with black contours. The vertical lines of the tree trunks organize the composition and establish a rhythmic structure that frames the surrounding landscape.

Through the use of overlapping forms, the foreground trees partially conceal distant buildings and vegetation. This arrangement creates depth without relying on traditional linear perspective. The intense red of the trees, contrasted with areas of green, blue, and yellow, gives the composition strong visual energy and reinforces the expressive character of the painting.

Fauvism was defined by bold, saturated colors and a focus on personal expression rather than realistic representation. Artists abandoned traditional techniques such as modeling and perspective, flattening forms and emphasizing the canvas’s surface. Line was used mainly to structure the composition, but color remained the primary tool of expression.

Fauvist works often depicted everyday subjects such as portraits, landscapes, nudes, and still lifes, but simplified shapes and dynamic arrangements made the scenes more about emotional and visual impact than literal appearance. Overlapping planes, strong contrasts, and rhythmic patterns guided the viewer’s eye and created a sense of depth without traditional perspective.

The experiments of this period, seen in works like Matisse’s “Woman with a Hat” and “Open Window,” Derain’s “Portrait of Matisse,” and Vlaminck’s “Landscape with Red Trees,” had a lasting influence on Matisse. They prepared him for “The Dance (La Danse)” (1909–1910), where he simplified the figures even further and emphasized large, colorful planes. Line and color merge into a dynamic whole, resulting in one of the most iconic images of modern art.

3) Dance by Henri Matisse: The Rhythmic Synthesis of Color and Movement

“Creativity takes courage.“ — Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse, the most recognizable leading figure of the Fauvist movement, was a bold and visionary artist born in 1869 in Cateau-Cambrésis in northern France. He initially studied law in Paris but soon abandoned his legal studies to devote himself fully to art. Matisse trained under several established artists, including Gustave Moreau, an important figure of the Symbolist movement, who became his teacher at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

Throughout his career, Matisse created many iconic works of modern art, including “Open Window,” “Blue Nude (Nu bleu),” and “Woman with a Hat”. His artistic practice was not limited to painting. He also worked in sculpture, drawing, and graphic arts, constantly exploring new ways of expression. Matisse remained creatively active for most of his life and continued working until his death in 1954, at the age of eighty-four.

One of the key milestones in Matisse’s Fauvist career came in 1909, when he received a commission from the wealthy Russian industrialist and art collector Sergei Shchukin. Shchukin asked Matisse to create three large-scale paintings intended to decorate the staircase of his residence, the Trubetskoy Palace in Moscow.

It is worth mentioning that Shchukin was one of the most important patrons of modern art at the time and played a crucial role in promoting and collecting works by artists such as Matisse and Picasso, helping to shape the development of early modernism.

One of the paintings Matisse created for Shchukin’s commission was “Dance I,” inspired by the Provençal folk dance farandole, which has pagan roots. The work is now housed at the MoMA in New York. Dance had always fascinated Matisse, not only for its beauty and grace but also for its expressive potential. He saw dance as a way to communicate emotions and feelings that could not be conveyed through words or other artistic means.

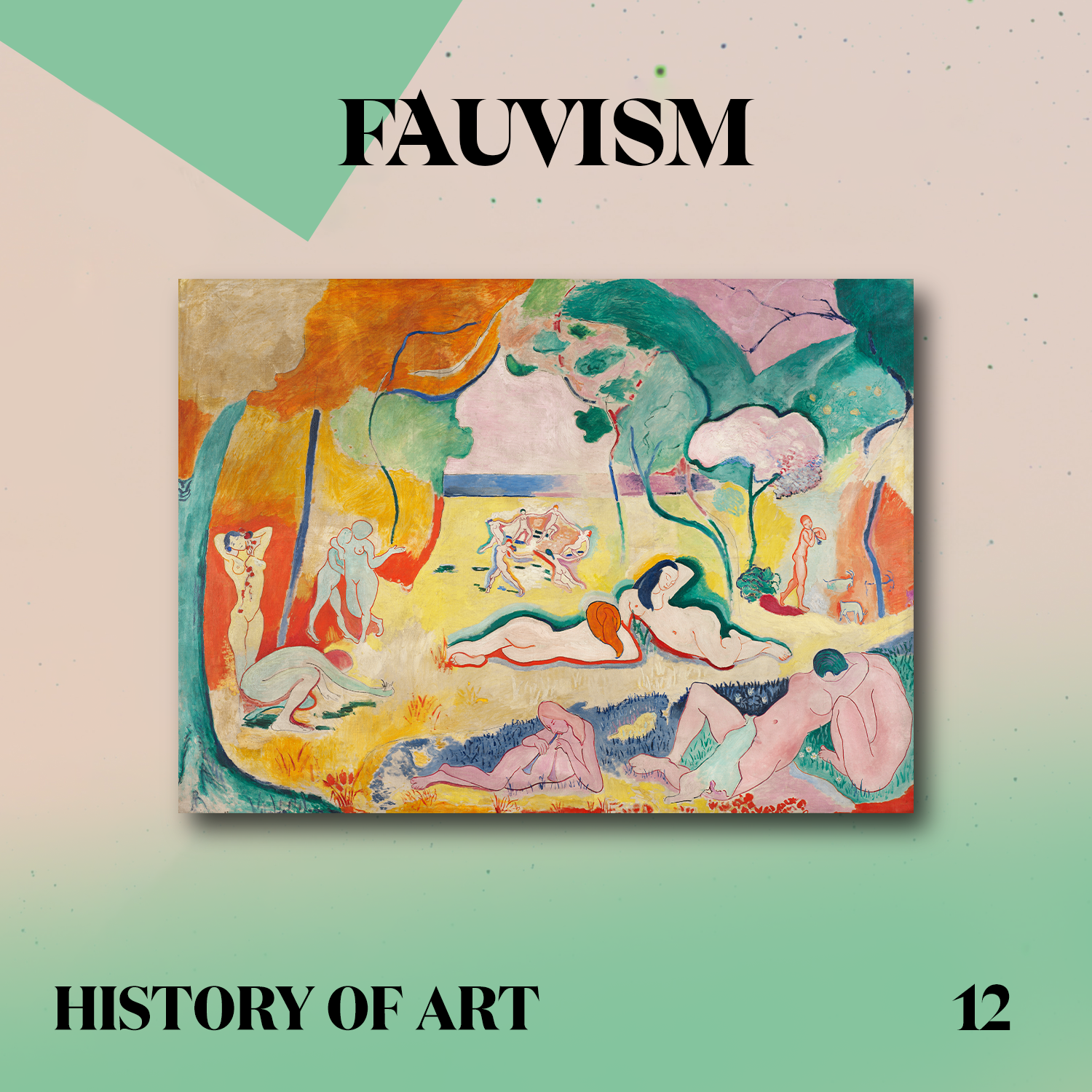

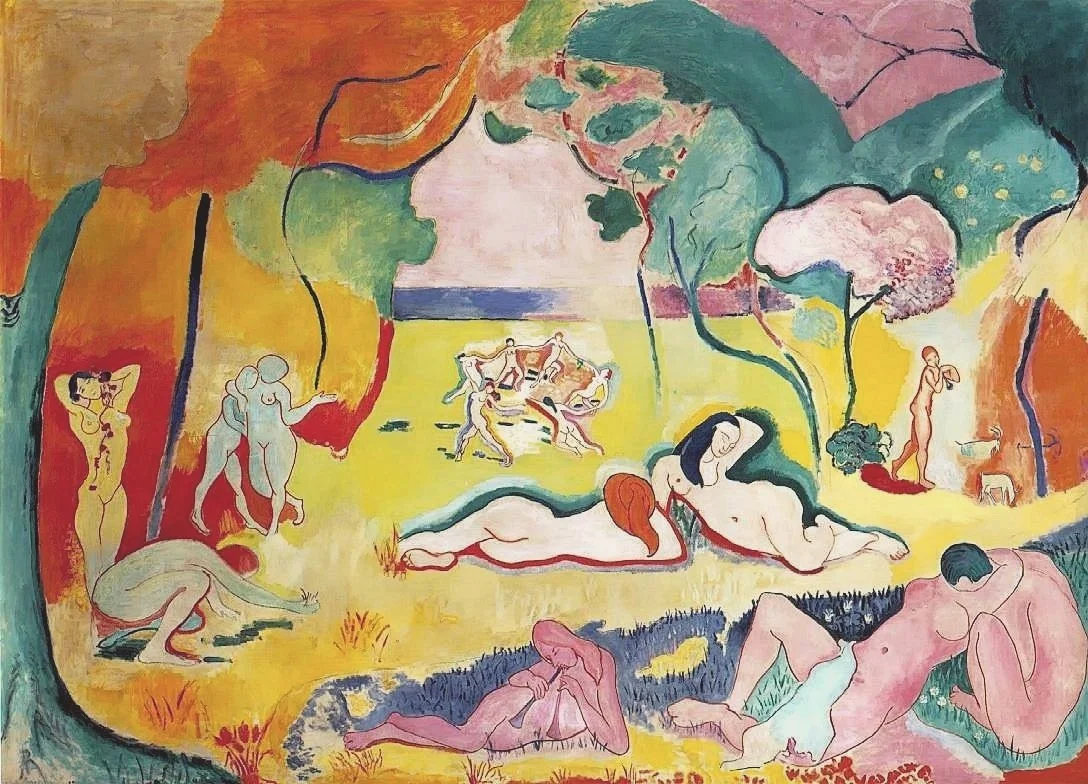

Matisse borrowed the dance motif from his earlier painting “The Joy of Life” (1905–1906), which he exhibited at the 1906 Salon d’Automne. This masterpiece is often considered a starting point for Fauvism. It is worth noting that Sergei Shchukin also visited the exhibition. He was reportedly captivated by a secondary element of the composition, showing a circle of bacchic dancers whose lively, expressive movements contrasted with the calm, idyllic atmosphere of the foreground.

Henri Matisse, The Joy of Life, 1905-1906 via Wikimedia, public domain

It is also important to note that Fauvism, as a movement, drew inspiration from many different cultural traditions, reaching back as far as antiquity. Henri Matisse was fully aware of the long history of the dance motif when he began working on this theme. The circular dance had appeared in European folklore for centuries, as a ritual invoking the gods, a dance of love, or a symbol of the cycle of the four seasons. For Matisse, however, one of the most important references may have been the stylized figures of dancers depicted on ancient Greek red-figure vases.

From folk dances, Matisse drew a sense of primal energy and spontaneous movement, while at the same time striving to reduce these forms to their simplest essence. He abandoned traditional perspective and the illusion of depth, creating a tense, ecstatic arabesque of bodies in motion. Only the outer contours of the figures suggest any sense of space, emphasizing the flatness of the painted surface.

On the painting “Dance I,” which he soon presented to his patron, Matisse enlarged this episode of the lively dance and brought it to the foreground. He completed the monumental canvas in just two days. However, the work was treated as a kind of exercise, a quick visual experiment showing how the motif could function and how movement might be conveyed on a static surface.

Painted with broad, spontaneous gestures, the work can be seen as a synthesis of Matisse’s many inspirations and a summary of years of artistic exploration. For a long time, he had been searching for a way to express dynamic movement within the stillness of a painted canvas.

Henri Matisse, Dance (I), 1909 via Wikipedia, public domain

In “Dance I,” the figures embody joy and physical pleasure, continuing a theme already present in Matisse’s earlier Fauvist works. The dancers are almost stripped of clearly defined contours that would precisely separate them from one another. Because of their simplified shapes and free, unrestrained movements, they may evoke associations with rag dolls. Their bodies appear flexible, weightless, and unrestricted.

This apparent childlike spontaneity, however, is deceptive. Matisse worked intensely to make his paintings appear effortless. One might imagine how different the effect would be if he had depicted rigid, frozen figures in the academic style of Jacques-Louis David. Such figures would hardly convey the same sense of pure joy and uninhibited movement. What Matisse achieved was in fact extremely difficult: he rejected traditional rules of figure representation and created an image in which form perfectly matches content.

In his conversations with Georges Charbonnier in the early 1950s, Matisse reflected on the relationship between movement and stillness in painting. He argued that movement does not require literal physical motion to be felt. A dance can exist both in the body and in the mind. Even within a static image, movement can be experienced intellectually and emotionally, engaging the viewer’s imagination rather than their physical participation.

“There are two way of looking at things. You can conceive a dance in a static way. Is this dance only in the mind or in your body? Do you understand it by dancing with your limbs? The static is not an obstacle to the feeling of movements. It is a movement set at a level which does not carry along the bodies of the spectators, but simply their minds.“

Henri Matisse, Dance (La Danse), 1909 via Wikipedia, public domain

Matisse deliberately plays with spatial ambiguity in “Dance (La Danse),” referring to one of the key ideas of modernist painting: the tension between depth and the flat surface of the canvas. The figures seem to move in a shallow, unreal space that resists traditional perspective, constantly reminding the viewer of the painting’s two-dimensional nature.

One of the most striking elements of the composition is the broken circle of dancers. The hands of two figures do not touch, creating a visible gap placed closest to the viewer. This interruption was introduced intentionally, so as not to disrupt the continuity of color and rhythm. The open circle has often been interpreted in two ways: as a symbol of tension seeking release, and as an invitation for the viewer to mentally enter the dance and become part of its movement.

In “Dance (La Danse),” Matisse sought to express life and rhythm in a radically simplified, abstracted form. He reduced the palette to a few intense colors, green, blue, and red, that are drawn from nature but do not imitate it. Color no longer describes reality; instead, it carries emotional energy and structures the entire composition.

The figures are not individualized. They function primarily as elements within a dynamic interplay of line, shape, and color rather than as representations of specific people. Matisse believed that photography, capable of recording reality quickly and precisely, freed painting from the duty of realistic imitation and detailed modeling. His aim was to communicate emotion as directly as possible, using the simplest visual means.

Despite the apparent simplicity of the scene, the composition is carefully calculated. Working within a limited pictorial space, Matisse created a sense of monumentality by presenting enlarged, fragmented bodies and guiding the viewer’s eye along their rhythmic movement. The viewer completes the image mentally, experiencing the work as expansive rather than confined.

Often described as the leader of the Fauves, Matisse used flat areas of color and thick, flowing contours to achieve a powerful visual clarity. “Dance” captivates through its reduction and openness. By stripping the image down to its essentials, Matisse posed a fundamental question: how far can form be simplified without losing emotional intensity?

Five figures dance in complete absorption, surrendering themselves to rhythm. Their bodies, rendered in strong red tones, appear muscular and energetic, each caught in a different phase of movement. Suspended between earth and sky, they inhabit an unreal space where color, motion, and emotion merge into a timeless vision of joy and vitality.

Summary

"I am unable to distinguish between the feeling I have for life and my way of expressing it." — Henri Matisse

Fauvism emerged in France as the first distinctly modern art movement of the 20th century. Its painters broke away from the dark, mysterious symbolism of the late 19th century period, capturing landscapes, still lifes, and human figures with bright, vivid colors and bold brushwork. Fauvist art emphasized emotional expression over realistic representation, using color as the primary vehicle for feeling and impact.

The early 20th century brought a wave of artistic innovation, as painters sought to reject traditional conventions and explore new ways of seeing. Realistic depiction was abandoned in favor of personal vision, inspired by nature but interpreted through the artist’s emotions. Fauvism, along with other avant-garde trends, embraced abstraction, rhythm, and simplified forms, seeking a modern language of art that was independent of the natural world.

Henri Matisse, André Derain, and Maurice de Vlaminck were the most prominent Fauves. Their work shows the influence of Post-Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism, particularly artists like Paul Signac and his color theories. Yet Fauvist painters abandoned the scientific approach of divisionism, focusing instead on the expressive power of color itself, applied freely and vividly, regardless of natural appearances. They also rejected traditional perspective, modeling, and chiaroscuro, flattening forms and emphasizing the two-dimensional surface of the canvas.

Fauvism’s interest in primitivism and non-Western art reinforced its reputation for boldness and intensity, earning its artists the name “wild beasts.” They explored direct and immediate means of visual expression, creating works that appeal to instinct and sensation rather than intellect. This search for simplified, stripped-down forms has continued to influence generations of artists, particularly in graphic design and logo creation, where clarity and impact remain essential.

It is worth noting that the experiences and experiments of the Fauvist period profoundly shaped Matisse’s later work. In “Dance”, he applied these principles to create a composition of even more simplified figures and large, vibrant planes of color. Here, line and color work together dynamically, producing one of the most iconic and influential paintings of modern art.

The Fauvist pursuit of bold, simplified forms continues to inspire generations of artists today, particularly in graphic design and logo creation, where clarity and visual impact remain essential.

If you found this article intriguing or are interested in collaborating, feel free to connect with me on Twitter or visit my personal website.