Exploring Edvard Munch: Anxiety, Symbolism, and the Human Psyche — History of Art #11

Edvard Munch, The Scream. Photo via Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Public Domain.

Edvard Munch (1863–1944) was a Norwegian artist who played a key role in shaping modern art during the transition from Impressionism to Expressionism. Although he cannot be classified strictly as an Expressionist, his work had a profound influence on the movement because of its emotional intensity and deep exploration of the human psyche.

Munch is often associated with Symbolism and Post-Impressionism, art movements that emphasized inner experience over external reality. Yet his influence reached far beyond these artistic boundaries.

His art defies simple classification, bridging the emotional depth of Symbolism, the psychological focus of Expressionism, and the formal experimentation of early modernism.

A central theme in Munch’s art was human emotion. His paintings often depict feelings of anxiety, loneliness, love, and the fragility of life. He aimed to express the psychological states that lie beneath the surface of ordinary experience. These emotional explorations became central to Expressionist art, which aimed to portray the world as felt rather than as seen.

“From the moment of my birth, the angels of anxiety, worry, and death stood at my side, followed me out when I played, followed me in the sun of springtime and in the glories of summer. They stood at my side in the evening when I closed my eyes, and intimidated me with death, hell, and eternal damnation. And I would often wake up at night and stare widely into the room: Am I in Hell?”

Munch also experimented boldly with form and technique. He often used unusual compositions and strong, unconventional colors to heighten the emotional impact of his scenes. This approach inspired later Expressionist artists, who similarly sought to break away from traditional realism in order to express inner truth through distorted forms and vivid tones.

Some of Munch’s works, most famously “The Scream,” contain elements that seem almost surreal. In this painting, the distorted landscape and the figure’s intense emotion convey a sense of existential terror that transcends the boundaries of realism. These surreal qualities anticipated later artistic movements that explored the subconscious and the dreamlike aspects of human experience.

Symbolism played a major role in Munch’s art. Rather than depicting life as it appeared, he used visual symbols to represent abstract ideas and emotions. His paintings often contain recurring motifs such as the moon, the bridge, or the human figure in isolation, which reveal deeper meanings about love, death, and the passage of time.

“My fear of life is necessary to me, as is my illness. Without anxiety and illness, I am a ship without a rudder. My art is grounded in reflections over being different from others. My sufferings are part of my self and my art.”

Munch’s work was deeply personal, rooted in the tragedies of his early life. The death of his mother and sister left a lasting mark on him, turning themes of sickness, loss, and mortality into a constant presence in his art.

By turning his private pain into universal imagery, Norwegian painter created works that resonated with the inner struggles of humanity. This emotional honesty and personal engagement with art later inspired Expressionist painters, who also sought to give form to their own inner experiences.

1) Biographical context

“Sickness, insanity and death were the angels that surrounded my cradle and they have followed me throughout my life.”

To understand the art of Edvard Munch, we must look at his life in Norway. His personal experiences shaped his artistic vision into a quiet but powerful scream of pain, expressed through a unique language of color and form.

Munch’s mother died of tuberculosis at only thirty years old, after giving birth to five children in just seven years. Edvard was only five at the time. Her passing marked the beginning of death’s recurring presence in his life and eventually became a central theme in his art. The children were then raised by their father, Christian Munch, a doctor from a respected Norwegian family of intellectuals, artists, and writers.

Among Munch’s ancestors were notable figures such as the painter Jacob Munch, the poet Andreas Munch, the bishop Johan Storm Munch, and the historian Peter Andreas Munch. Yet despite this intellectual heritage, Edvard’s childhood was marked more by sorrow than privilege.

His father, devastated by the loss of his wife, fell into deep melancholy and religious fanaticism, which cast a shadow over the household. The only source of warmth came from their aunt, Karen Bjølstad, who became a maternal figure to the children.

Another devastating loss came when Munch was fourteen, when his beloved older sister Johanne Sophie died of tuberculosis in 1877. Her death left a permanent mark on him, and the themes of illness, fear and death followed him for the rest of his life.

In his notebooks, which often contained reflections to accompany his paintings and prints, Munch described a deep sense of dread and anxiety that had haunted him since childhood.

“Art comes from joy and pain...But mostly from pain.“

After his sister’s death, Munch blamed both his father and God. In 1880, when he was seventeen, he rejected religion and began searching for his own view of the world. That same year, he wrote in his diary that he had decided to become a painter, a decision that would shape his life and give expression to his deepest feelings.

Munch’s first significant paintings were "Self-Portrait" (1881), "Young Girl Lighting a Stove" (1883), and "Morning" (1884). At the age of twenty, he took part in a group exhibition in Christiania (now Oslo) for the first time in June 1883.

Edvard Munch, Morning, 1884 via Wikimedia, public domain

"Morning" (1884), originally titled "A Servant Girl," depicts a young woman sitting quietly on the edge of her bed as daylight fills the room. The soft light and calm atmosphere evoke a sense of solitude and reflection, capturing the quiet moment between night and day.

While the scene appears simple, it carries a subtle sense of loneliness. Even in this early, naturalistic style, Munch was already searching for something beyond mere representation. He was beginning to explore the inner life and hidden struggles of the human soul.

Beneath its apparent simplicity, "Morning" reveals the tension between innocence and confinement, demonstrating the young artist’s growing sensitivity to psychological depth. This early work foreshadows the introspective and emotionally charged approach that would define his later, more mature paintings.

2) Artistic beginnings

Edvard Munch, together with artists such as Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, is regarded as one of the forerunners of Expressionism. This movement aimed to convey the inner world of the artist, emphasizing feelings, emotions, and psychological states over external appearances. Expressionists sought to show what it felt like to experience life, not just what it looked like.

To achieve this, Expressionist artists replaced technical perfection with emotional intensity. They used vivid colors, simplified forms, and strong contrasts to create a more direct impact on the viewer. Munch’s work perfectly illustrates this approach.

Norwegian painter often combined energetic brushstrokes with both complementary and temperature-based contrasts. By using dynamic compositions and deliberately distorting shapes, he aimed to express a felt emotion rather than simply depict reality.

“Expressionism is not a style but rather an attitude toward life. It is a way of viewing consciousness, rather than ideas, a way of viewing the universe of which the earth is only a part.“

Edvard Munch, The sick child, 1886 via Wikimedia, public domain

A central example of Munch’s early Expressionist approach is "The Sick Child" (1886). In this painting, he moves away from realism and naturalistic approach toward a deeply personal style. The scene shows a young girl on her sickbed, rendered with intense colors and contrasting tones that heighten the emotional impact. Munch simplified forms, used diagonal and curved lines, and applied energetic brushstrokes, sometimes exaggerating or distorting elements to express grief and anxiety rather than merely depict reality.

"The Sick Child" also reflects Munch’s broader concern with human vulnerability, mortality, and emotional intimacy, central themes that would define his later work. It demonstrates how he transformed private pain into a universal language of emotion, paving the way for his Symbolist and Expressionist projects. Later critics recognized it as one of the most important works in Norwegian art history.

It’s worth adding that the term Expressionism comes from the Latin expressio, meaning “to express.” Applied to painting for the first time by Julián-Auguste Hervé, french painter who.

It described art that aimed to communicate inner feelings rather than portray the visible world objectively. In this sense, Expressionism was not a single style but a way of seeing the world, one that emphasized emotion, personal truth, and the psychological experience of modern life.

For Munch, this approach became a natural language for expressing themes of anxiety, desire, loss, and vulnerability.

Through these early works, Munch developed a visual language capable of expressing inner life and human emotion. His exploration of color, form, and composition laid the groundwork for his later masterpieces and influenced the broader Expressionist movement across Europe.

3) Symbolism, and Secession

In 1889, Edvard Munch held his first solo exhibition in Kristiania, presenting 110 works. He faced harsh criticism, yet for the first time, he was recognized in Norway as an artist with a rich and distinctive expressive style. The exhibition established him as a leading figure of the third generation of Norwegian artists and helped him secure a government scholarship for a three-year study in Paris. With the support of several influential avant-garde painters, Munch trained in the drawing studio of Léon Bonnat at the École des Beaux-Arts.

At the end of 1889, Munch received the belated news of his father’s death. Grieving, he moved from Paris to the nearby town of Saint-Cloud, and due to health issues, he also stayed in Le Havre and Nice. During this period, he lived in memories and limited social contact, befriending only the Danish poet Samuel Goldstein, who shared similar early love experiences and reflections on mortality.

Together, Goldstein and Munch helped define symbolism as an alternative to naturalism in art. Originating in the latter half of the 19th century, Symbolism first appeared as a term in 1886 in a manifesto published in the French newspaper Le Figaro.

A group of French poets sought to convey emotional and spiritual truths through symbols rather than literal representation. They believed that the world perceived by humans is only superficial, and deeper truths lie beyond the grasp of reason or the senses. Symbolist art instead expresses these truths through multilayered, ambiguous imagery rather than conventional, realistic depiction.

One of Munch’s earliest and clearest engagements with Symbolism was "The Kiss" (1890). In this painting, he depicted for the first time a standing, faceless couple locked in a tender yet unsettling embrace.

Edvard Munch, The Kiss, 1897 via Wikimedia commons, public domain

This painting marks a transition from his early naturalistic work toward a more abstract and emotionally symbolistic yet universal visual language. The lovers, almost veiled as if behind a fog, are not specific individuals but representatives of countless couples across generations. Munch revisited this theme several times, each version showing slight variations. A notable version from 1897, held in the museum in Oslo, illustrates his continued fascination with the emotional and psychological dimensions of love.

The faceless forms are key to the painting’s symbolic meaning. By removing individual identity, Munch transforms the kiss from a simple depiction of a real-life encounter into a universal symbol of intimacy, emotional fusion, and the loss of self. The dark, shadowy room isolates the couple from the vibrant world visible through the window, emphasizing their detachment from reality and highlighting the inward intensity of the moment.

This abstraction and focus on inner experience through universal themes exemplify Symbolism. The painting does not record a literal event but conveys truths about love, desire, and human connection through emotional resonance. The merging of faces can also be interpreted as a warning about the loss of individuality; love is depicted as a consuming, almost parasitic force that creates unity at the expense of the self.

Beyond its immediate visual impact, "The Kiss" is a meditation on memory. The blurred, featureless faces evoke the way experiences fade over time: one remembers the emotional weight of an embrace, while the physical details dissolve.

In this sense, Munch paints the very essence of the act, transforming the kiss into a timeless phenomenon. Through its abstraction and symbolic depth, the work illustrates how Munch helped shape Symbolism by emphasizing mood and inner life over literal representation.

“Nature is not only all that is visible to the eye... it also includes the inner pictures of the soul.”

It is worth mentioning that after developing his Symbolist vocabulary in works like "The Kiss", Munch’s art of the mid-1890s began to show certain formal affinities with the rising aesthetics of Secession. Although he did not belong to the movement, and in fact remained deeply independent, some aspects of his visual language coincided with tendencies explored by Secessionist artists across Europe.

Edvard Munch, Madonna, 1894-1895 via Wikimedia commons, public domain

Secession, emerging in the 1890s as Art Nouveau in France and Jugendstil in Germany, marked a conscious break with academic classicism. Its hallmark features included flowing, organic contours, asymmetry, ornamental line, stylized figures, and motifs inspired by nature and Japanese prints. These qualities reflected a broader modernist attempt to create a unified visual language across painting, design, and the applied arts.

Munch did not adopt Secessionist principles in a systematic or decorative way. Instead, the parallels between his work and Secession arise from his search for expressive, simplified contours capable of carrying psychological and symbolic meaning.

The emphasis on the rhythmic, curving line, especially in his lithographs and paintings from 1894–1896, creates a visual kinship with Secession, even though its purpose in Munch’s work remains profoundly different: more existential than ornamental, more emotional than decorative.

This becomes especially evident in "Madonna" (1894–1895). Here, the sinuous outline of the woman’s body, the undulating flow of her hair, and the organic, halo-like shape surrounding her suggest a formal proximity to Art Nouveau linework. Yet the work ultimately transcends decorative stylization.

It transforms the traditional sacred theme into a modern symbol of eroticism, vulnerability, creation, and mortality. In "Madonna", therefore, Munch demonstrates how a visual idiom that resembles Secession can be redirected toward psychological intensity and Symbolist meaning. Rather than reflecting the movement, the painting shows how Munch’s independent exploration of line, form, and emotion intersected, briefly and productively, with the wider artistic currents of his time.

Although Munch’s exploration of line in works like "Madonna" occasionally intersected with the aesthetics of Secession, his artistic trajectory was moving toward a more radical and intensely personal vision. By the mid-1890s, he focused on distorting form, intensifying color, and translating inner turmoil into visible signs.

This evolution culminates in what would become his most iconic work, "The Scream", where psychological crisis and existential fear are transformed into a universal, almost tangible presence on the canvas.

4) The Scream: A Vision of Modern Anxiety

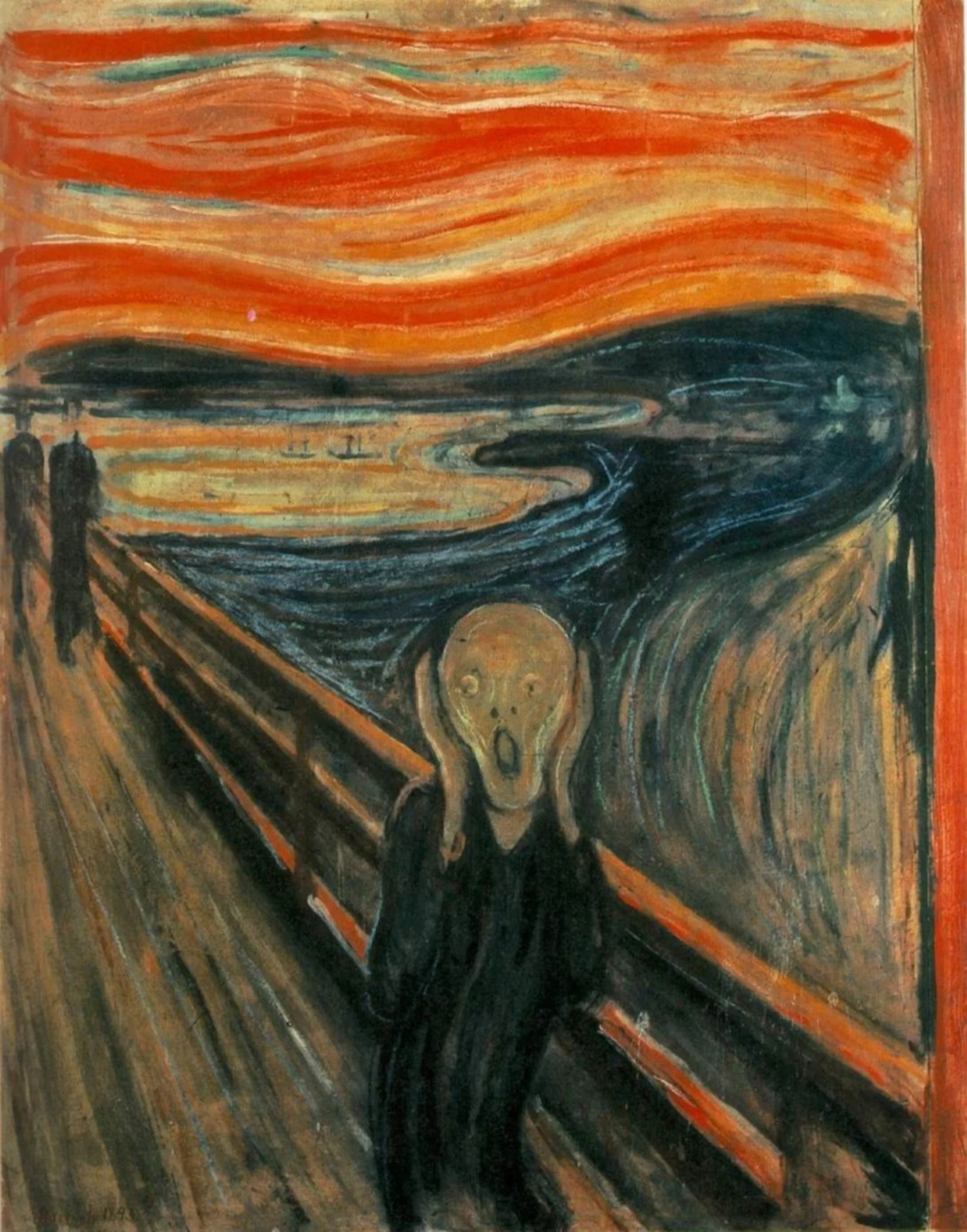

Among all of Edvard Munch's works, "The Scream" holds a special place. It is one of the most recognizable images in the history of art and one of the clearest examples of how Munch transformed personal experience into a universal visual language.

Like Leonardo da Vinci’s "Mona Lisa," it has entered popular culture, endlessly quoted, parodied, and reproduced. Yet where the "Mona Lisa" conveys controlled, enigmatic calm, "The Scream" expresses raw, uncontrollable psychological turmoil. While the "Mona Lisa" invites contemplation and subtle reflection, "The Scream" confronts the viewer with raw, uncontrollable human anxiety.

In both cases, the surrounding landscape shapes the meaning of the central figure, but in Munch’s painting, the environment itself seems to mirror inner distress.

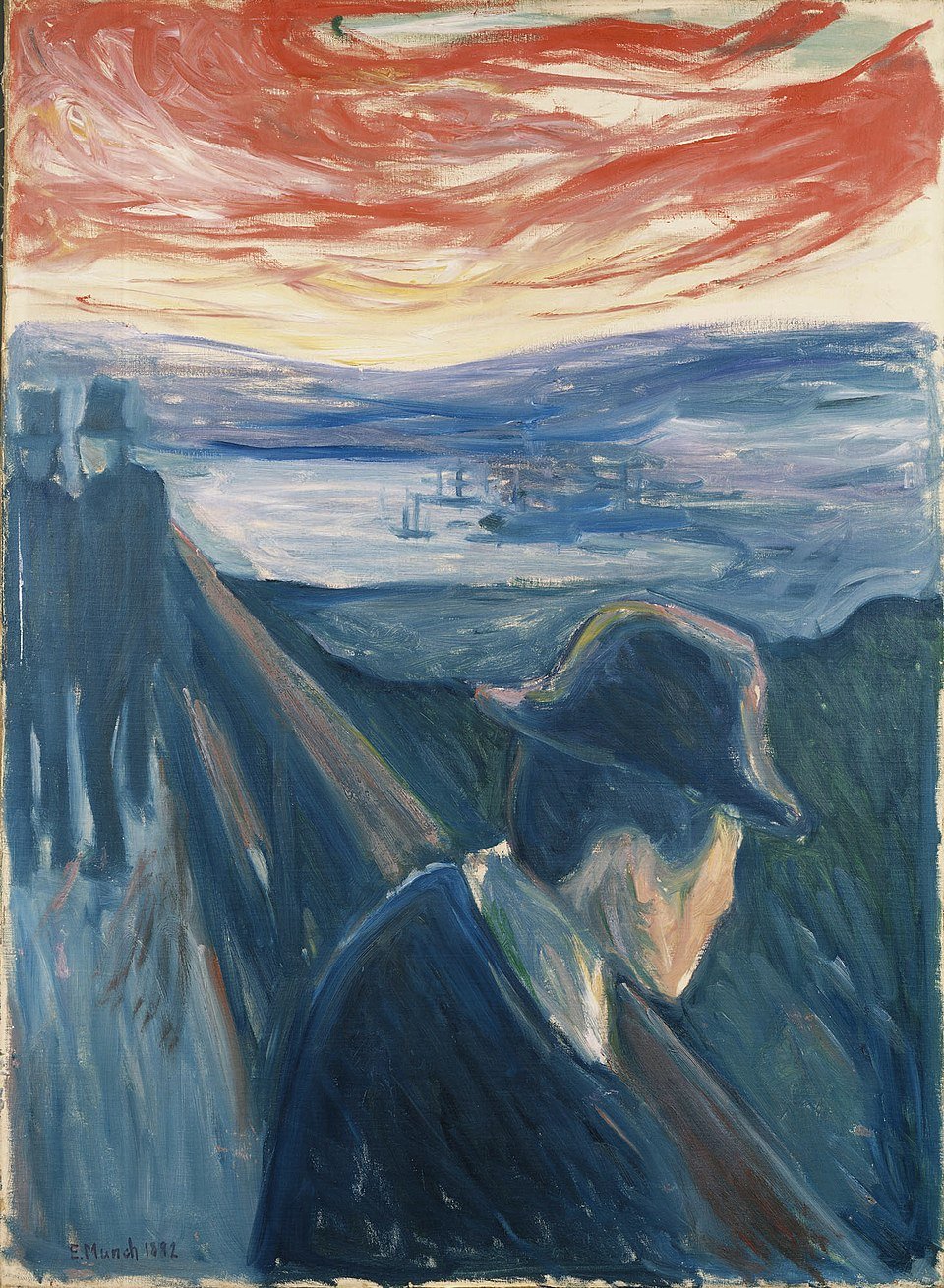

It’s worth adding that before "The Scream" reached its final, iconic form, Munch explored similar ideas in an earlier work titled "Despair" (1892). This painting can be seen as a direct precursor to "The Scream."

Edvard Munch, Despair, 1892 via Wikimedia commons, public domain

It uses the same bridge composition, but the central figure is different: instead of the deformed, universal figure of "The Scream," "Despair" shows a man wearing a hat. The emotion in this earlier work is quieter and more introspective.

"Despair" shares key elements with "The Scream," such as the diagonal bridge and flowing landscape, but soft, wavy strokes and muted blues, grays, and earth tones create a calmer, more reflective atmosphere.

The figure emphasizes contemplation and individuality, while the receding landscape mirrors his inner state. In many ways, "Despair" allowed Munch to experiment with compositional elements, color modulation, and the portrayal of emotion. These were experiments he would later amplify in "The Scream".

In this sense, "Despair" serves as a stepping stone to "The Scream," where these elements are intensified into a universal expression of anxiety.

The origins of "The Scream" lie in a real moment from Munch's life. As he wrote in his diary:

"I was walking down the road with two friends when the sun set; suddenly, the sky turned as red as blood. I stopped and leaned against the fence, feeling unspeakably tired. Tongues of fire and blood stretched over the bluish black fjord. My friends went on walking, while I lagged behind, shivering with fear. Then I heard the enormous, infinite scream of nature."

This sudden panic, triggered by an unusually intense red sunset over the Oslo fjord, became the emotional core of the painting. At the time, Munch's sister was confined in a nearby psychiatric hospital, adding a personal layer to the fear he experienced. His friends continued walking, indifferent, while Munch stopped, frozen in panic.

The painting mirrors this contrast: two figures move forward calmly, while the central figure remains paralyzed in terror.

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893 via Wikimedia commons, public domain

The figure itself is not meant to represent a specific person. Munch removed individual features, gender, and age, turning it into a universal symbol of human vulnerability. Contrary to common belief, the figure is not screaming. Instead, it covers its ears to block out an overwhelming "scream of nature" that vibrates and distorts the world under psychological pressure.

The painting’s structure reflects this inner turmoil. The sharp diagonal of the bridge suggests order and solidity, while the sky and water are painted with flowing, wavy lines that seem unstable and expressive. The intense red sky conveys shock, danger, and emotional collapse, and also hints at anxieties of modern urban life and industrialization.

Munch painted "The Scream" on unprimed cardboard, avoided varnish, and even exposed some works to the elements, the so-called "horse cure", allowing nature to leave marks on the surface. This rawness underscores the emotional intensity of the scene and amplifies the tension between human fragility and overwhelming external forces.

"The Scream" became central to Munch's cycle "Frieze of Life," exploring love, fear, illness, and death. One version bears a faint inscription: "Could only have been painted by a madman," reflecting both public criticism and the artist’s psychological vulnerability.

The bridge frames the swirling landscape like a cage, placing the viewer in the figure’s position amid a world that seems to ripple and break apart. Childhood trauma, fear of illness, and lifelong anxiety inform the painting, making it a culmination of Munch’s recurring themes: loneliness, panic, and the fragile boundary between sanity and madness.

The painting's lasting power comes from its simple forms and emotional depth. As the wavy lines vibrate and the red sky evokes a sense of catastrophe, the image becomes a universal metaphor for fear and isolation. It captures both personal anxiety and the overwhelming pressures of a rapidly modernizing world.

Summary

“Vis atque metus,” strength and fear, could serve as the motto of Edvard Munch’s art. He explored human emotion without restraint, breaking rules and crossing boundaries. Far from adhering to a programmatic Expressionism or any single artistic movement, he created a deeply personal visual language that transformed inner experience into universal meaning.

Munch’s work laid the foundation for modernist painting by shifting attention from mimetic representation to psychological and existential exploration. For the Norwegian artist, art became a medium for projecting subjective emotional states, anxiety, and the awareness of mortality. By synthesizing influences from Symbolism and the aesthetics of Secession, he developed innovative forms and lines capable of conveying emotion and inner life.

Works such as "The Kiss" demonstrate his use of abstraction, faceless figures, and emotional intensity to represent intimacy, desire, and the loss of self. "Madonna" (1894–1895) reveals his engagement with flowing lines and organic forms reminiscent of Art Nouveau, yet redirected toward psychological and Symbolist meaning rather than decorative effect.

Munch’s paintings visualize inner experience rather than external reality. Trembling lines, unnatural colors, and fluid forms create a world destabilized by emotion, in which landscapes and objects resonate with human anxiety.

This vision reaches its fullest expression in "The Scream," where existential fear becomes a universal symbol, and the external world mirrors internal turmoil. Ultimately, Munch demonstrates that anxiety is not merely a backdrop to human existence but a fundamental and enduring element of the human psyche. His art transforms personal experience into a universal language of emotion, making the invisible structures of the mind visible.

Through his work, Munch proves that fear, longing, and ecstasy are not only individual experiences but shared and timeless aspects of the human condition.

If you found this article intriguing or are interested in collaborating, feel free to connect with me on Twitter or visit my personal website.